As we celebrate the XX European Day of Languages we look at some interesting facts about writing systems of the past and present.

The letters of the alphabet were invented almost four thousand years ago, in Mesopotamia, to speed up communication: drawing objects to be sold or exchanged wasted precious time for trading. Over the past thirty years, we have been reintroducing pictograms into our writing. This time mainly to express emotions and feelings.

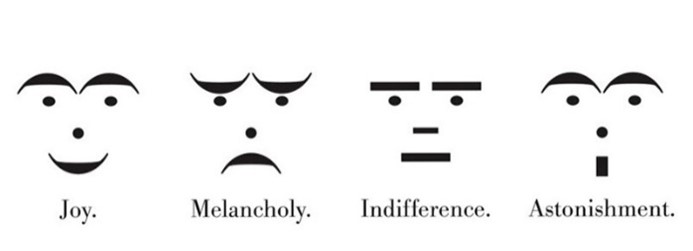

Emojis can help create a more empathetic world, for all of us says Adobe’s 2021 Global Emoji Trend Report. After all, it’s clear to anyone that writing “I can’t wait to go 😎” means anything but “I can’t wait to go 😒”. Beloved by boomers and millennials alike, over 3,000 emojis abound our everyday communications. Icons depicting food, nature and various objects have increased in recent years, but the favorites are still the faces. The same Adobe report indicates the categories that users would like more of are primarily ‘emotions and feelings’ followed by ‘relationships’. The first appearance of ‘smilies’ probably dates back to March 1881 when four stylized faces were published in the American satirical magazine Puck, as a demonstration of typographic skill.

Eighty years later, in 1963, the commercial artist Harvey Ball designed the first big yellow smiley we all know: it was used by an insurance company for an internal communication campaign. After being cleared through customs in the computer world in the 1980s, emojis have become increasingly popular; so much so that in 2015, Oxford Dictionaries chose a smiley as the ‘word’ of the year (😂). An increasingly fast and concise digital media has undoubtedly contributed to the success of emoji, but the transformation of writing could also be linked to the content we want to convey. Are we lacking words to express emotions? Or are personal and social changes easier to portray this way?

👨👩👦👨👩👧👨👩👧👦👨👩👦👦👨👩👧👧👩👩👦👩👩👧👩👩👧👦👩👩👦👦👩👩👧👧👨👨👧👨👨👧👦👨👨👦👦👨👨👧👧👩👦👩👧👩👧👦👩👦👦👩👧👧👨👦👨👧👨👧👦👨👦👦👨👧👧

How an ox became an A: the evolution of the alphabet

Around 1700/1500 BC, communities in Mesopotamia began to gradually abandon pictograms – symbols depicting a thing – in favor of a writing system in which each symbol corresponded to a sound. Prior to the birth of letters as we know them, symbols that were an evolution of Egyptian hieroglyphics were used, but with trade becoming more and more extensive, recording transactions needed be faster – one could not waste precious minutes drawing rows of sheep or sheaves of wheat. This early writing system called Protosinaitic, was the basis for the formation of several various alphabets: Hebrew, Aramaic (and from there the Arabic and various Indian alphabets) and Phoenician. Phoenician led to Greek, and from there to Cyrillic and Latin – an alphabet that appeared in around 600 BC and is now used by some 50 languages worldwide. In some of the letters we use today, the original pictogram can still be recognized.

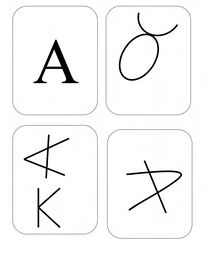

The A as we know it comes from the first letter of the Protosinaitic alphabet: alef. Alef was also the word for ‘ox’, which in turn stood for agriculture, our forebear’s main source of livelihood and the reason for its position of priority at the top of the alphabet.

In ancient Egypt, a hieroglyph in the shape of a bull indicated the same thing. Over time, the drawing became simpler: the horns were flattened until they ‘slid’ over the head. At the time of the Phoenicians, several symbols were used contemporaneously; the Greeks transformed aleph into alpha and the symbol was turned 180°. Via the Etruscans, these letters reached the Romans, where they underwent a further simplification process eventually evolving into the Latin writing system.

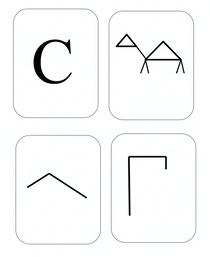

Another example related to an animal is our C, which derives from the third sign of the Protosinaitic alphabet and originates from the word gamal, which meant ‘camel’.

This animal was, and still is, very important in desert areas as it was able to transport water through arid regions and withstand long periods of drought. For the symbolic representation, the part that is the most important feature was chosen: the hump. This sign was very simple and quick to represent compared to its Protosinaitic equivalent and as such, was later adopted by the Hebrew alphabet. In the Greek writing system, the symbol was rotated and straightened later becoming today’s gamma. For the Latin alphabet it was further simplified and revolved 90˚, thus becoming the symbol for the sound ‘C’ or alternatively ‘K’.

China simplifies in its own way

While transformations of the Egyptian writing system were emanating from the Mediterranean, the Chinese system, which still today combines a symbol with a word to become an ideograms or, more correctly: logogram, flourished in the Far East. It wasn’t that the Chinese populations of the past had less need for speed than their counterparts over the ‘pond’, their simplification of characters had already begun in ancient times for practical reasons: for example, the sun was initially engraved on pottery or metal tablets as a circle, then when pottery became replaced by bamboo leaves, the sun circle changed shape and assuming the form of a square – it was very difficult to draw curved symbols on bamboo.

The real game changer came about once paper was introduced and people began to write with brushes and ink in around the 2nd century AD. With these tools it was easier to enrich the characters and Chinese calligraphy, as we know it today, was born. It was the Communist Party, who in 1945, imposed a new simplification of characters to reduce illiteracy, especially in the countryside..

Since then, the simplified form of about 2,000 words is China’s preferred choice, whilst traditional characters remain the preserve of academic circles. In Taiwan and Hong Kong, as well as in some Chinese communities in Canada and the United States, the rejection of these characters has a political flavor, refunsing what is decided by the communist government in Beijing.

🙂 or ^_^ ?

For a few years now, many people have been wondering if emojis could open a new chapter, making language barriers obsolete – well, apparently not entirely.

First of all, we need to clarify the difference between emojis, emoticons and kaomoji. Emojis are ‘written’ in Unicode computer language and are widely used on computers and smartphones. Unicode is a universal character encoding system used by various digital communication platforms, so the final appearance of the drawn faces is effectively the same – or at least very similar – all over the world.

On simpler devices and if you can’t or don’t want to use a graphical interface, you use either emoticons which are typically used in the West or kaomoji, the Japanese variant. Emoticons and kaomoji are smilies ‘drawn’ only with letters and punctuation. Emoticons are read from left to right and comprise a maximum of four characters: for example 🙂 for a smile. Kaomoji, on the other hand, are read from the front and can consist of up to 20 characters: for example ^_^ but also (*^▽^*), which indicates an even greater joy.

But diversity is not only due to computer languages. Pictograms are a condensation of culture.

Returning to smiles; the difference between emoticons and kaomoji can be explained by the fact that in the West, the smile is primarily associated with the mouth: 🙂 or :-D. In Japan, the focus is on the eyes. This is even more evident in the depiction of a woman’s smile: ^.^. The mouth is only one point, because showing teeth for women was once traditionally frowned upon in that part of the world.

≦(._.)≧ – This is also an icon that is difficult to understand without cultural context. Kaomoji also represent body parts and in this case, we are seeing a deep bow, a common gesture of apology in Japan. Seen like this, ‘I can’t wait to go ≦(._.)≧’ takes on even yet another nuance. . .

Where not expressly indicated by links, the information contained in this article has been taken from teaching materials developed by the SMS – One school, many languages project research team.

Author: Valentina Bergonzi

First published on Eurac Research Magazine on 23 September 2021